What Makes Other Countries’ Trading Tick?

As most of you know, we have studied quite extensively (some would say too much) how round lots and tick sizes affect trading and stock valuations.

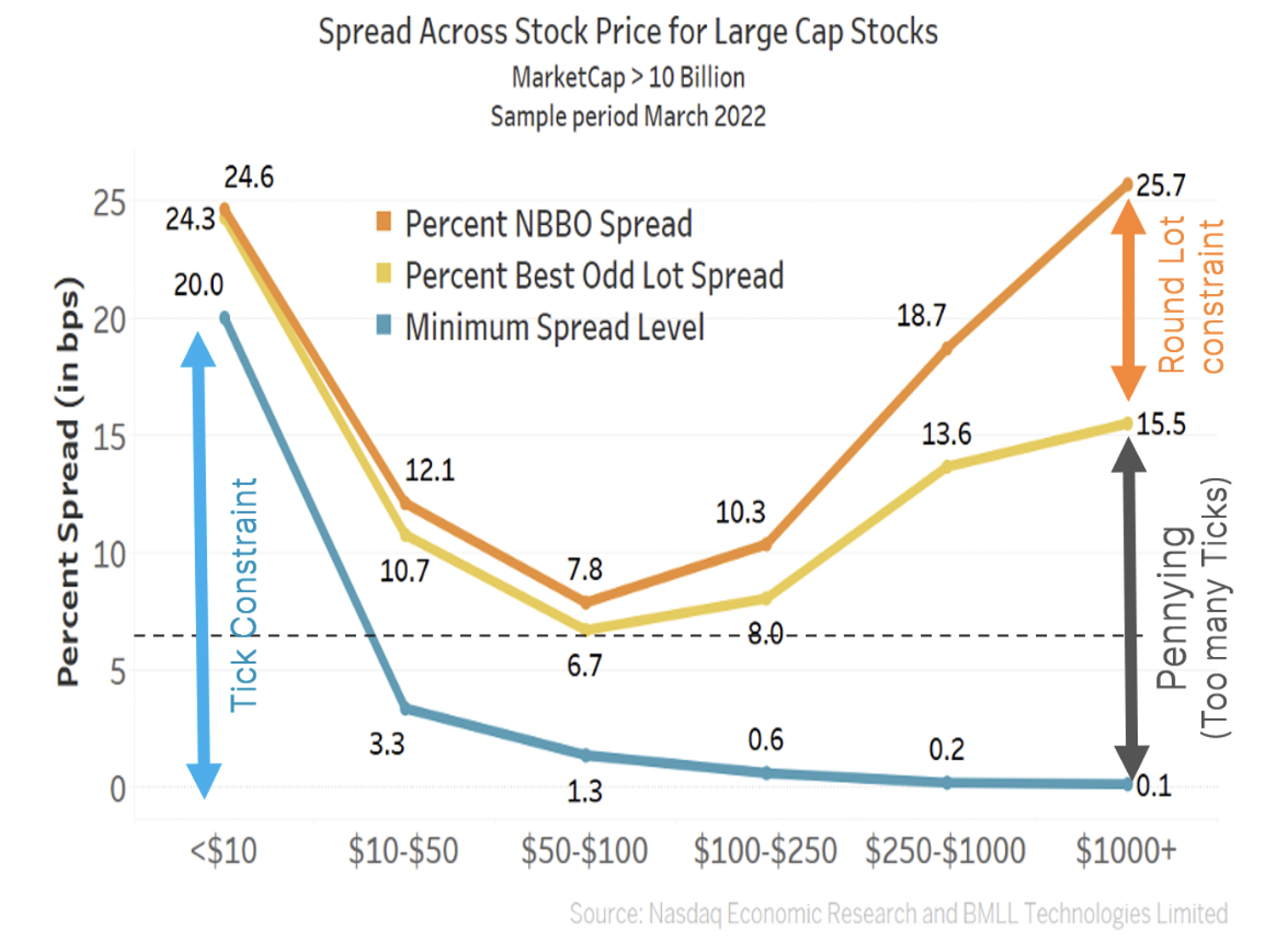

In short, a one-size-fits-all tick creates unnecessarily wide spreads on low-priced stocks. The “tick constraint” problem. At the other end of the spectrum, economically de minimus ticks combine with round lot constraints to create pennying and round lot constraints that lead to odd lots, which inflate NBBO.

Chart 1: The U.S. system of round lots and 1-cent ticks creates inefficiency as stock prices rise and fall

But there is still more data to share on this topic!

Today we use a database maintained by the World Federation of Exchanges to look at how other countries do ticks and lot sizes.

What we find is the U.S. system of 100-share round lots and 1-cent ticks is actually quite unusual.

For simplicity, you will see that we refer to cents and dollars. We know different countries have different currencies, and some (like Yen) do not have aggregate 100 cents into a dollar-like increment.

Most countries have eliminated the odd-lot problem

It turns out that the majority of countries, including all of Europe, have eliminated the odd lot problem by moving to 1 share round lots (Chart 2 and Table 1).

That would seem rational in this era of automated trading. Especially when the majority of orders in some stocks already ignore the round lot conventions, and fractional share trading is new and increasing.

Chart 2: Round lot sizes by country

Many use ticks to make depth tradable

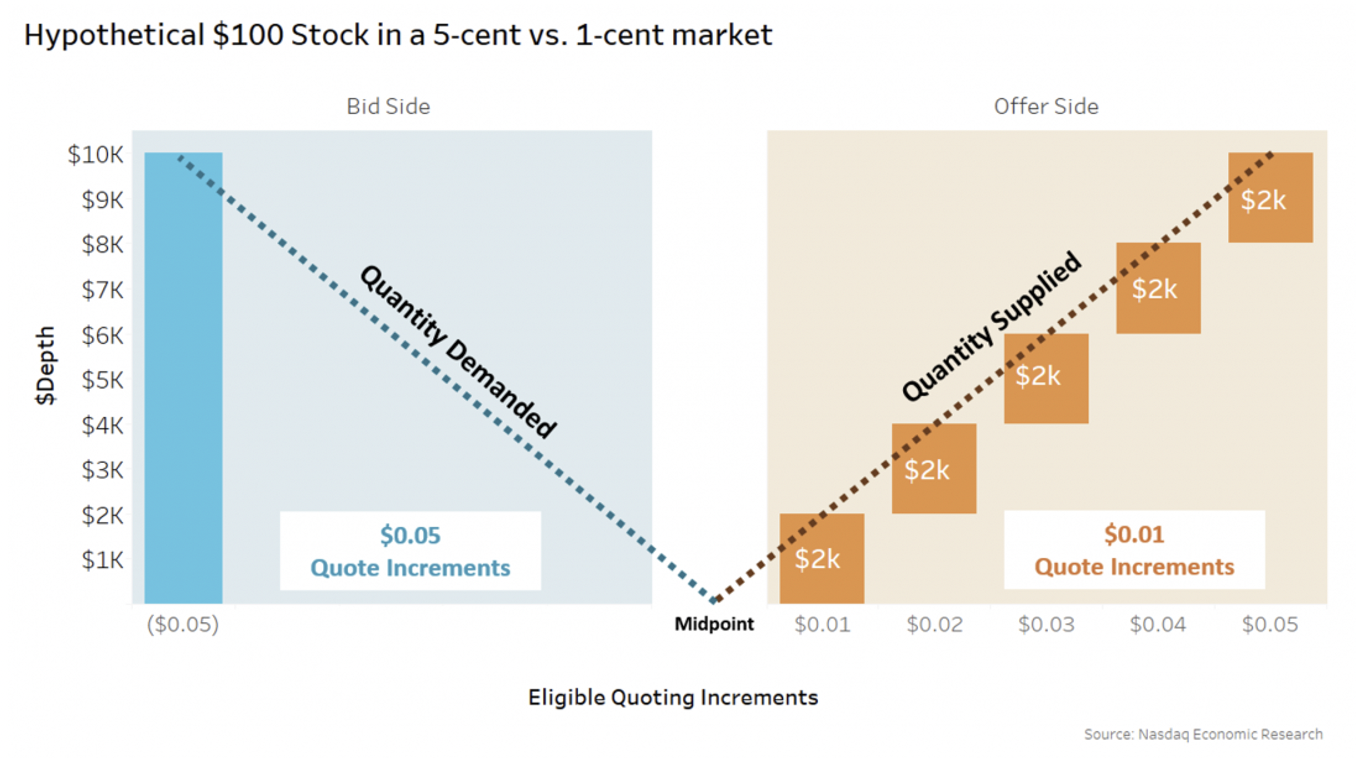

Of course, 1-share round lots could cause a “depth problem,” where the NBBO might be made of only 1-share. That could make computing execution quality complicated when average order sizes these days are closer to $8,000.

We could start by highlighting that the real impact of eliminating round lots on depth is likely less impactful than that – based on how odd lots are used now.

However, another way to ensure 1-share trades don’t set NBBO too much is to ensure there aren’t too many “ticks” (or levels) inside the NBBO where small orders can rest. In short, a more dynamic tick regime forces queues to form at more consistent (economic) intervals – rewarding price setters and making queue jumping more expensive.

As we know from the tick pilot, supply and demand of liquidity form in a V-shape (Chart 3), and tick size has little impact on the slope of the curves (how much liquidity is available as you move away from mid). But ticks affect the price points where it aggregates.

As we show in Chart 3, “too many ticks” (right side) could result in very small depth at multiple levels. This is important given the inside quote forms the NBBO that is used to benchmark trades – as “trade throughs” would occur on most marketable trades hitting the offer side of this chart.

In contrast, as the tick pilot found, a 5-cent tick forces all the orders to aggregate at the single available price point. That, in turn, increases depth at the inside quote. Importantly, this shows we can use ticks to target a specific value of depth. So ticks can be used to fix both the depth and pennying problems.

Chart 3: The tick pilot showed that tick increments can be used to change NBBO depth

Not many countries tick and trade like the U.S.

There are a number of different ways round lots are treated around the world. The data in Table 1 shows that many countries have eliminated round lots:

- In MSCI Developed markets, only five countries (including the U.S.) trade with round lots.

- Almost half of the Emerging and Frontier markets (42%) also have eliminated round lots.

- Only three other countries use variable round lots, as the U.S. has proposed in NMS-II. Hong Kong lets companies pick their round lot sizes, while Canada has even larger round lots for very low-priced stocks. The Philippines has seven different round lot groupings, increasing in shares as prices fall to create a more consistent round lot value.

Looking at tick regimes, we see a wide variety of approaches too – ranging from a one-size-fits-all tick to as many as 19 different tick groups – with the more complicated tick regimes popular in Europe and Asia.

Chart 4: Number of tick groups (by country)

Although one tick group is the second most popular category, with 11 countries having a one-size-fits-all tick, it is far more common in MSCI Frontier and standalone markets (78% or seven countries).

Interestingly, all countries break their additional tick groups out by stock price; however, there are different ways to deploy those groups:

- Many markets are like Hong Kong, with a single tick schedule for all stocks. However, we know that smaller stocks typically have wider spreads for the same price as larger stocks.

- Japan and Korea account for this by having two tick groups, one with smaller ticks for larger stocks.

- Europe, which includes 27 countries, has developed a much more complicated version of this with six different liquidity groupings, each with 19 different tick groups. Similar to other countries, Europe also sets many breakpoints for tick changes at repeating increments of 1, 2, 5 (10, 20, 50, etc.). That allows most stocks to trade very close to the “optimal spread 1-3 ticks wide,” which their research has confirmed is optimal.

Technically, the U.S. has two tick groups, as stocks with a price under $1 trade with ticks of 1/100th cent (0.01c). However, stocks with such low prices are also in breach of listing rules and must reverse split or appreciate to avoid delisting – so it includes relatively few stocks.

China also has more than one tick regime; however, that’s because some stocks trade in HKD or USD (in addition to RMB).

Kazakhstan trades in 1-cent increments except for some securities with prices dependent on the central bank.

Table 1: Lots and ticks by country

It is interesting to see the way variable tick regimes increase. Most have increments in multiples of 1, 2, 5 and 10 – where every larger increment is roughly double the prior increment. That helps keep spreads closer to the 1-3 ticks that many have found to be optimal.

Why is this important?

We all know odd lots and tick sizes are a problem in the U.S.

Data suggests getting them right could reduce trading costs, simplify the market, boost liquidity and, in turn, increase valuations. That’s all good for U.S. capital formation and U.S. investors.

Ironically, changes to ticks at first glance seem to add complexity. Although in reality, creating variable round lots was a far more radical step by regulators.

Looking at the rest of the world, we see that, far from being complex, eliminating round lots and creating dynamic ticks may bring us into line with how most of the rest of the world already trades.